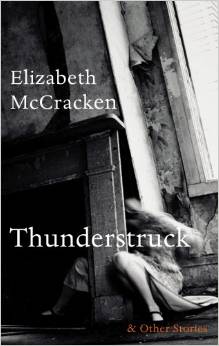

Elizabeth McCracken is the author of An Exact Replica of My Imagination, The Giant’s House, Niagara Falls All Over Again and two short story collections Here’s Your Hat What’s Your Hurry and Thunderstruck and Other Stories. A former public librarian, she now holds the James Michener Chair of Fiction of the Michener Center for Writers, at the University of Texas, Austin. Her work has been shortlisted for the National Book Award and she was also chosen as one of Granta‘s 20 Best American Writers Under 40. Elizabeth is currently shortlisted for The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award for her story Hungry and recently won the prestigious The Story Prize for her latest collection Thunderstruck and Other Stories.

McVeigh: You’ve been teaching throughout most of your writing career, what is it about teaching that keeps it such a constant in your life?

McCracken: For years I tried to avoid permanent teaching work, largely because I love it and find it consuming. So I got a graduate library degree and worked as a librarian, and I took a lot visiting jobs in MFA programs. The job I have now, at the University of Texas, Austin, is the first full-time permanent teaching job I’ve ever had. I teach in two graduate writing programs here (a bit of an oddity that there are two at UT); I have terrific students and colleagues. I loved my writing teachers as both a graduate student and undergraduate–among them Sue Miller, George Starbuck, Derek Walcott, and Allan Gurganus–and I want to try to replicate what they gave me: serious attention, rigorous reading, impatience when I was showing off for no good reason. I really love reading other people’s work and trying to make it better–my talent as a teacher, such as it is, is that I am either the smartest dumb reader ever, or the dumbest smart reader. At any rate, I enjoy articulating why a piece of fiction works or doesn’t work for me. The drawback is that I get much less writing done than I did when I worked full-time as a librarian, since teaching and writing use the same mental real estate.

McVeigh: You spent time travelling in Europe and living in France (Thunderstruck & The House of Two Legged Dogs are set there) and I was wondering if that time impacted on your writing on a deeper level too. Do you recognise a European accent in your writing voice, in subject matter or sensibilites?

McCracken: I’m sure it has changed things, and not just because of the whole pants/trousers divide. I now actually know English geography (whereas 15 years ago I wouldn’t have known Sussex from Suffolk). Paris is no long imaginary to me. Denmark is actual. More to the point, perhaps, displacement is no longer imaginary to me, and I think I write about that a lot more–both Americans displaced in Europe, and Europeans displaced (I’m working in a story right now that involves Germans in Galveston, Texas). I feel I understand more about the curve of the globe than I once did–both how big the world is and also how small.

McVeigh: Your husband is playwright and novelist Edward Carey (I saw ‘Captain of the Birds’ many years ago at London’s Young Vic) what is it like having two writers in the house?

McCracken: It’s remarkably easy. We’re important readers to each other but we’re very careful not to have our fingers in each other’s work in early states–we don’t really talk over work-in-progress till we have drafts done. When I hear about partenered writers who talk fondly of exchanging each page of writing, I get nervous. I’m not sure why. It’s like wearing the same underpants and bragging about it. Years ago I heard a husband & wife team who gave a reading in which they alternated reading sentences, and it remains one of the most revolting spectacles of my life. Still, I’d read Edward’s work before I met him (he’d read mine, too), and I’d loved it, absolutely. Having the writer of that book (Observatory Mainsions) and all his subsequent work around is fantastic. It would be terrible to live with a writer whose work I thought was only all right.

McVeigh: Your recent collection ‘Thunderstruck & Other Stories’ has received widespread acclaim and recognition from prizes – ‘Hunger’ currently shortlisted for The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award. How important do you think awards are to a writer’s career and has it impacted on you personally?

McCracken: Oh, prizes are lovely and terrible and random. As a reader prizes are handy–there are a lot of books I hear about for the first time because they’ve won or been shortlisted for a prize. Two of my favorite books of the past few years by two dear friends–Tinkers by Paul Harding and A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing by Eimear McBride–became huge successes after they won prizes, so in that way, yes: I’m in favor of prizes. But as a writer, I can’t them too seriously.

McVeigh: When it comes to creating a collection, how do you decide which stories make it in and how do you go about ordering them?

Mostly I don’t think about a book as I write: I write one story at a time, let them mass up, and then pit them against each other. If two stories seem very similar, I get rid of the one I’m less sentimental about. I think in the end I wrote about twice as many stories over the years the book spans than actually found their way into the book.

After that, it’s nearly a crossword puzzle. I don’t want two stories that seem too similar right next to each other–there are a lot of kids in Thunderstruck, for instance, so I tried to distribute them through the book. The title story is the last story I wrote, and it’s much longer than the rest, so it made sense for it to go at the end.

McVeigh: It’s clear you have a love of language. You experiment with form, point of view (rare in a short story) and you bring humour where it isn’t expected, the overall impression I get is that you are really enjoying yourself. And it’s infectious. Are you really enjoying yourself or is it hard work to create the appearance of playfulness?

McCracken: That’s lovely to hear. The answer is: writing, for me, is a joy and a hoot and a pleasure and a misery and a punishment from God. It’s really never anything in between. I do think that pleasure in writing transmits to the reader, even if not exactly: the lines that make me laugh out loud are not really the ones other people find funny. When I give readings I’m always surprised by what gets laughs and what gets crickets–I have been known to pause dramatically after a line that I think is hilarious only to be met with silence. I revise a lot but I’m not somebody who labors over sentences–for me, a sentence that needs a lot of work is a sentence that should be tossed aside. The labor, for me, goes into plot and structure, getting rid of pointless characters who exist only to show off their wit, making characters speak to each other more interestingly. Hm. As I type this I realize the real answer is: the language comes fairly easily to me. It’s everything else that’s hard.

McVeigh: We often hear that we should write everyday. Do you have a writing routine?

McCracken: Lord, no. I should try to get a better one going. On the other hand, I’ve never written every day. For months at a time: yes, every day, though even at my times of highest productivity I took Sundays off, working on one of my most deeply held beliefs about writing: it’s like weightlifting. In this case, that means you must schedule days of rest or else you’ll injure yourself. (Another similarity: you can’t train yourself to lift heavy weights by lifting small weights, no matter how many repetitions.) When I’m writing well, I block all internet access so that I can’t hear the chatter of the rest of the world. I work long hours. For those people for whom write every day is good advice, more power to them. As for me, I try to think of what I’d like to get accomplished within a month, or three months. I try to imagine how angry I’ll be with myself if I don’t get that work done. If I told myself to write 1000 or 100 words a day, I would freeze up.

McVeigh: I still have moments when I question if I’m a writer at all and I was interested to hear your thoughts on the matter in an interview. Would you share how you respond to this?

McCracken: Yes. And–as with any writing malady–the only cure is work. If I work I don’t worry about it. If I’m avoiding work or caught up with some other aspect of life, I doubt myself tremendously. If I manage to work I feel better almost instantly.

McVeigh: When you look back at your work are there stories that are your favourites? Are there some you are less enamoured with over time?

McCracken: Oh, yes. There’s still one story in my first collection that I think isn’t very good. For the most part, I become fond of older work–I’m able to think, Well, it was the best I could do at the time. But I’m often surprised when people like stories that I think are thinner than others. My favorite stories tend to be a matter of sentiment–where I was at the time that I wrote it, or the circumstances of my life. “Something Amazing,” from Thunderstruck, is always going to be one of my sentimental favorites. So will “Peter Elroy: A Documentary by Ian Casey” even though I get the sense that it’s nobody else’s favorite. Maybe especially because I don’t think it’s anyone else’s favorite.

You can also read my interview with Laura van den Berg one of the judges who awarded Elizabeth The Story Prize.

Some links to find out more about Elizabeth McCracken.

Elizabeth McCracken Has the Best Laugh – podcast interview.

A Conversation with author Elizabeth McCracken by National Endowment for the Arts on PRX – podcast interview.

Episode 326 – Elizabeth McCracken | OTHERPPL WITH BRAD LISTI – podcast interview.

NEA Literature Fellow Elizabeth McCracken | NEA – podcast and transcript.

Stories by Elizabeth McCracken published in Zoetrope: All-Story:

Birdsong from the Radio, Vol. 17, No. 3

A Dream of Being Sufficient, Vol. 16, No. 3

The House of the Two Three-Legged Dogs, Vol. 11, No. 1

The Lost and Found Department of Greater Boston, Vol. 13, No. 4

sidebar: An American in Paris, Vol. 10, No. 3

Something Amazing, Vol. 12, No. 1

A Dream of Being Sufficient, Vol. 16, No. 3

The House of the Two Three-Legged Dogs, Vol. 11, No. 1

The Lost and Found Department of Greater Boston, Vol. 13, No. 4

sidebar: An American in Paris, Vol. 10, No. 3

Something Amazing, Vol. 12, No. 1

Pingback: In the Media: 12th April 2015 | The Writes of Woman

Pingback: Elizabeth McCracken Interview | The Good Son

Thanks for finally talking about >Elizabeth McCraken | The Good Son <Loved it!

LikeLike

You’re welcome.

LikeLike